Social disparities in child obesity: a report from the STOP project

Social disparities in child obesity: a report from the STOP project

World Obesity is a partner in the EU-funded STOP project, which ended in November 2022. The outcomes include a better understanding of the importance of family affluence to reduce the risk of childhood obesity, how low income can undermine weight management outcomes, and which policies might be successful in reducing socio-economic disparities in obesity. Tim Lobstein reports.

Social disparities in child obesity in Europe are getting worse

The last three decades have seen a dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in the European region.

This increase has not been uniform across families, however, with evidence that social determinants such as household income, parental education, parental profession, or measures of area deprivation can be strongly associated with prevalence levels.

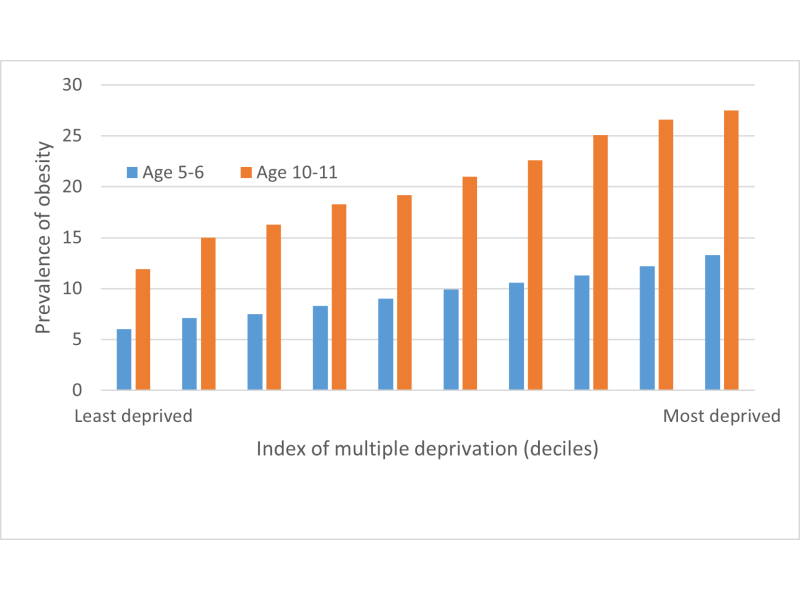

Some of the clearest evidence comes from the English National Childhood Measurement Programme, which weighs and measures all children in their first and last year of primary education, and analyses the results according to the locality in which the children’s families live, using a composite measure of neighbourhood deprivation. The data show a remarkably consistent gradient in obesity prevalence across the entire range from least to most deprived neighbourhoods (see Figure 1). The data here are for 2019, before the COVID-19 epidemic, which we will return to shortly.

Figure 1. Child obesity prevalence at age 5-6y and 10-11y according to a composite neighbourhood deprivation measure.

Source: NCMP 2019/2020, Public Health England 2021.

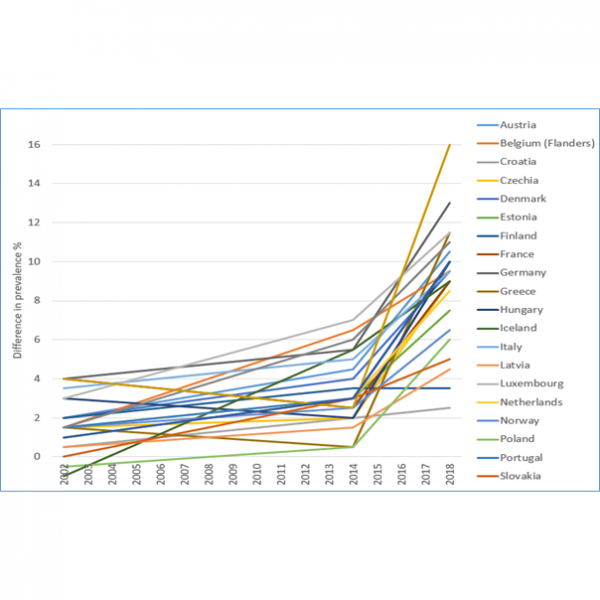

The difference in obesity prevalence between the most deprived decile and least deprived decile is 7.3% and 15.6% for younger and older children respectively. The most deprived children have more than twice the prevalence of obesity than the least deprived. And the difference has been increasing dramatically across much of Europe, as successive Health Behaviour of School-Age Children surveys have demonstrated. Figure 2 shows the extraordinary increase in the difference in just 4 years, from 2014 to 2018, across virtually all of the 20 European countries surveyed.

Figure 2 (right). The difference in the prevalence of obesity between adolescents (aged 11-15y) in less affluent families and those in more affluent families.

Source: Health Behaviour of School-Aged Children surveys, 2002, 2014 and 2018.

COVID-19 has increased the disparity

Many countries around the world have reported an increase in childhood BMI during the COVID-19 epidemic, suggesting reduced physical activity, increased screen time and poorer diets might be likely causes. Surveys run during the main period of ‘lockdown’ (starting in early 2020) indicate a rapid rise in obesity prevalence for all children (see Cena et al), but this may be especially the case for children in less affluent households (see e.g. Titis).

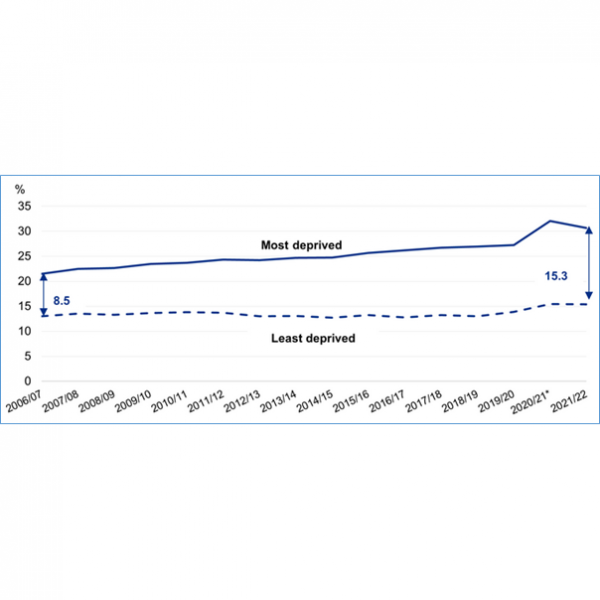

Figure 3 (left). Child obesity prevalence at age 10-11y showing trend in disparity between most and least deprived households, including the COVID-19 ‘lockdown’ period.

Source: NCMP 2021/2022

Most recently there is some evidence that this rise in obesity prevalence may have abated but the disparity between socio-economic households has widened. The data for England shown in Figure 3 illustrate this clearly. For children aged 10-11y, the gap in obesity prevalence between the most and the least deprived children grew to 16.6 percentage points in 2020/2021 and then declined to 15.3 percentage points in 2021/2022. As can be seen, this still shows a widening gap from pre-COVID years which appears to have been aggravated and then partially ameliorated during the epidemic.

It is remarkable if this decline in obesity prevalence, if it is confirmed, should happen so rapidly, within a year of lockdown conditions easing. Why should prevalence levels fall at all, let alone so soon, given the difficulty most countries have reported in the last two decades in reducing child obesity prevalence, particularly for children in lower-income households?

STOP project outcomes: paediatric treatment

Several reports from the STOP project have clarified the issues around disparities between children from different levels of household or neighbourhood affluence. In principle, child obesity prevalence can be reduced through successful treatment for children who have developed obesity as well as through policies that prevent children from developing the disease. However, this raises the question of whether availability and access to paediatric weight management services are accessible, acceptable and sustainable to all families that need them.

As the World Obesity Federation has previously reported services for adults are patchy and inconsistent in the region. They are likely to be so for children as well, and may only be accessible to those that persist in requesting them.

In the STOP project as systematic review of social disparities in clinical obesity treatment for children found a disturbing lack of information. Despite the importance of social determinants as a driver of child obesity risk, there is a significant lack of research into the influence of social disparities on health care participation and outcomes for children with obesity. While there is evidence that access to services, sustained attendance, and successful outcomes are affected by a family’s attitudes to overweight, their motivation to make family-level changes, and the resources to make and maintain these changes, these have not been linked specifically to household or neighbourhood affluence.

This is a large research gap, which could easily be filled. Most of the papers assessing paediatric obesity treatment will record family socio-economic characteristics a baseline, but then they report the outcomes after adjusting for socio-economic status. This is a major lost opportunity to assess the outcomes looking specifically at the effects of socio-economic status. Retrospective analyses, and a requirement from funding agencies that research should include assessment of the differential effects of interventions according to the families’ status.

Social disparities also need to be considered in the design of treatment protocols: interventions need to be culturally and socially sensitive, avoid stigma, encourage motivation, recognise barriers that families face and develop novel approaches to maximise benefit. Furthermore, from the experience during the COVID epidemic, health care providers should ask parents about challenges they have experienced, including changes in economic and housing security, as well as clinical vulnerability. Understanding household resilience and vulnerability will allow treatment providers to explore what forms of intervention are likely to be successfully sustained, tailoring their advice to individual households, and supporting parents to enact positive change even in difficult circumstances.

STOP project outcomes: prevention of childhood obesity

At family and community level, STOP reviews showed that walkable neighbourhoods and neighbourhoods with more playgrounds are associated with lower obesity prevalence and that areas with more vegetation, less population density and without major roads are associated with improved health behaviours in childhood. Furthermore, higher consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with a faster rise in BMI in childhood.

Data reported in the STOP project showed that in specified circumstances children from low income families were more responsive to behavioural ‘nudges’ than children from high income families. For example, in high income families children were 17.5% less likely to select fruit than children from low income families when required to pre-order lunchtime meals. When pre-ordering was combined with a prompt to consume healthy foods, 46% of children from low income families changed their order to healthier options compared to only 21% of children from high income families. In another intervention, introducing incentives for fruit and vegetable consumption in school cafeterias was more effective in schools with a greater proportion of low-income children compared to schools with a smaller proportion of low-income children.

Population level policies may be more effective at sustained change for lower income families. A STOP systematic review concluded (a) health-related taxes would reduce socio-economic disparities in child overweight; (b) promotional marketing restrictions would also reduce social disparities in child overweight; but that (c) front-of-pack labelling has not been sufficiently studied in children to make a prediction on the differential impact across socio-economic class. There is also a lack of information on digital marketing channels in terms of children’s exposure, differentiated across household income, parental education or ethnic group.

The differential impact of policies depends on several factors including underlying disparities in exposure to risk, disparities in the reach and sustainability of policies, and disparities in vulnerability to risks and in responses to policy interventions.

STOP analysis: levies or taxes on sugary foods

In the case of fiscal interventions, such as a tax on sugar-laden foods or beverages, literature reviews have found very little information on differential price elasticities according to socio-economic sub-groups, or for household with children. In the STOP project, specially commissioned food purchasing data were used to calculate the price elasticities for high, middle and lower income households, and for households with children of various ages or no children, and these indicate consistent findings across France, UK and Spain:

- (a) consumption of sweet biscuits and of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated negatively with household income (a higher consumption is associated with lower income);

- (b) own-price elasticities tend to be greater for lower income households for these products (consumption would reduce more for lower income families per unit rise in prices than it would for higher income families); and

- (c) own-price elasticities show no significant variation according to the presence or absence of young or older children in the household.

These findings indicate that a rise in the price of sugar-sweetened foods would lead to a greater drop in consumption among lower income families, and that the presence of children would make little difference to this response. However, these pilot findings need to be replicated across more products and more countries, and work on cross-price elasticities (how much a change in the price of one product leads to a change in consumption of a different product) to ensure that unintended effects can be foreseen.

Additional policies to promote

Besides the three policy areas investigated by the STOP project – taxes, labelling and advertising – others are also being proposed. For example, the Best-ReMaP project is looking at standards for the public procurement of food, and also at opportunities for re-formulating food products, while the recently completed Policy Evaluation Network project has assessed a wide range of policies being implemented in the region.

However, one of the problems faced in all public health interventions is a lack of research into the experience of ill-health in lower-income families, and the experience of the policies and interventions being proposed or implemented. This raises questions on how the voices of people – especially children – can be heard and represented in research programmes and in policy development.

Projects such as CO-CREATE are exploring methods for involving adolescents in obesity policy development, but even this project has found it hard to ensure that they can reach young people from socio-economically deprived and under-represented families. And while websites designed to appeal to younger people have been developed, such as the WOF-sponsored Healthy Voices site it is still impossible to know whether the messages such websites disseminate are being received by young people in more deprived families, or what effect the messages have, or whether something very different is needed.

The STOP project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 774548. The present blog reflects only the author’s view.